Chasing the Storm

Chasing the Storm

Anthony Amore’s Quest for the Missing Gardner Museum Masterpieces

Rembrandt’s “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee” is one of 13 works of art stolen in 1990 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the largest art heist in U.S. history.

Thirty-five years ago, two thieves impersonating Boston police entered the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and stole half-a-billion-dollars’ worth of art. Anthony Amore ’89 has spent 20 years searching for the art, and he’s more determined than ever to find it.

By Marybeth Reilly-McGreen

Some things you might not know about stealing masterpieces:

- The perpetrators aren’t Thomas Crown types rappelling from ceilings and diving under infrared rays with the dexterity of ballet dancers.

- Priceless art theft is more likely to happen during the day because museums are alarmed at night, making stealing infinitely more difficult.

- Scotland Yard, Interpol, and the FBI will be called, of course, but stolen art generally stays local—stashed on, say, a pig farm or under a friend’s bed.

- Eighty percent of art heists are inside jobs.

- Selling stolen art is hard. Buying it is a criminal act, which eliminates most of the demand for multimillion-dollar artwork. So, in a real sense, “priceless” stolen art is worthless.

These are some of the lessons that come from spending an afternoon with Anthony Amore ’89, director of security and chief investigator of Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

2025 marks the 35th anniversary of the largest art heist in history. Amore has spent the last 20 years searching for 13 works stolen from the Gardner, pieces by artists so legendary we need only know their last names: Degas, Manet, Rembrandt, Vermeer. Today, the 13 pieces are valued at between $500 million and $1 billion. The Vermeer alone has an estimated value of $250 million.

There’s a $10 million reward for information leading to the recovery of the paintings. And though the FBI announced more than a decade ago (2013) that they knew who stole the artwork, the perpetrators have not been named, nor has the artwork been recovered. In 2015, the bureau announced that the thieves were dead, but still did not identify them. The FBI, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, and, of course, Amore, are still seeking leads as to the whereabouts of the art.

Anthony Amore ’89, director of security and chief investigator at the Gardner Museum. Behind Amore is a portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner painted by John Singer Sargent in 1888; the portrait is on display in the museum’s Gothic Room.

The crime:

At about an hour after midnight on March 18, 1990, two men posing as Boston police entered Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, bound and gagged its two college-aged security guards, and stole 13 pieces of art. Of the 13 works, the piece of greatest notoriety is “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee” (1633), Rembrandt’s only seascape.

Amore has a particular affinity for that painting.

“‘The Storm on the Sea of Galilee’ is a story about faith, and I think it’s a perfect allegory for my work,” says Amore, a devout Catholic. “I have to have faith that I can recover these paintings. If I lose faith that I could do it, I should leave the job.

“You have to operate in the realm of hope.”

Vermeer’s “The Concert” and Rembrandt’s “A Lady and Gentleman in Black” are among the works stolen from the Gardner Museum collection in 1990.

Amore is arguably the world’s foremost expert on art theft. He came to the Gardner with an impressive résumé in federal law enforcement. After URI, he became an inspector and port intelligence officer for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Immigration and Naturalization Service and then took a position with the Federal Aviation Administration’s security division, assigned to five New England-area airports, including Boston Logan International Airport. After earning a Master of Public Administration degree at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, he went into security, consulting for a time, but 9/11 spurred Amore to return to government work. In 2001, he became assistant federal security director for screening and regulatory inspections at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, serving in that role for four years.

In 2005, Amore became director of security and chief investigator at the Gardner.

In addition to his work for the museum, Amore has written national bestsellers about art heists: Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists (with Tom Mashberg), The Art of the Con: The Most Notorious Fakes, Frauds, and Forgeries in the Art World, and The Woman Who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist. Amore co-teaches a graduate class, Art Crime: Investigations and Implications, in the museum studies program at Harvard University, and he is also a popular guest lecturer in URI’s Forensic Science Seminar Series.

In November 2025, Simon & Schuster will release Amore’s fourth book: The Rembrandt Heist: The Story of a Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship, which chronicles the life of one of the world’s most notorious art thieves, Myles J. Connor Jr., one of Amore’s close friends.

Yes, you read that right. Amore’s decades-long hunt for the stolen artwork has earned him the respect of Boston’s criminal element, in addition to law enforcement. Major broadcasting outlets, such as the BBC, NBC, CNN, and NPR, also seek his expertise on security and terrorism issues. Journalist and friend Kelly Horan, deputy editor of the Ideas section of The Boston Globe, calls him a “one-man walking brain trust.”

“Anthony has a natural self-confidence. He commands attention. And you need to have that because you’re dealing with expert con men.”

—Kelly Horan, deputy editor, The Boston Globe

“He is our Sherlock and Watson rolled into one,” says Horan. Amore is featured prominently in Last Seen, a 10-episode podcast produced by Horan that premiered in 2018 on WBUR, a Boston NPR station.

“Anthony’s won the trust of such an array of people. To do what Anthony does, you cannot be closed-minded. You cannot be arrogant. You cannot look down on anybody,” Horan says.

“Nor can you tremble in the presence of anybody,” Horan adds. “Anthony has a natural self-confidence. He commands attention. And you need to have that because you’re dealing with expert con men.

“This is a tale of two cities: You’ve got the world of high art and the world of crime, and you have to be able to move between those two worlds and be respected. Be trusted.

“And Anthony Amore is,” adds Horan.

You Have to Be Willing to Speak to the Devil

Located at 25 Evans Way in the Fenway neighborhood of Boston, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is a palatial building with Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, Roman, and Romanesque features. It houses a multibillion-dollar collection of more than 2,500 items, including paintings, tapestries, sculptures, furniture, rare books, and ceramics.

Gardner was an American heiress and art collector who, after her father died in 1891, used much of her $2.75 million inheritance (about $78 million today) to build her world-class art collection—and an equally stunning repository for it. Dubbed “America’s Most Fascinating Widow” by The New York Journal and Advertiser, Gardner ran with America’s artistic elite. Artist John Singer Sargent and author Henry James were her close friends. And novelist Edith Wharton attended the New Year’s Day opening of Gardner’s museum in 1903, though she called the champagne and donuts served “fit for a provincial French train station,” according to the 2022 book Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life.

Gardner’s will stipulates that everything in the palace remains where it is, which is why some of the most dramatic sights in the museum are the empty gold gilt frames in the museum’s Dutch Room, frames that formerly held Rembrandt’s “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee” and “A Lady and Gentleman in Black,” and Vermeer’s “The Concert.”

“It’s like being a homicide detective and walking by a chalk outline every day for 20 years,” says Amore.

In his investigative work, Amore has interviewed thousands of people, including hundreds of criminals. They don’t scare him. There is truth to the saying that criminals have a code, Amore says.

“I grew up in Providence, amongst that sort of element. Both of my brothers served time in prison. As a child, I would be on Federal Street sitting on the stoop with my grandmother, and Raymond Patriarca would walk by and tip his hat to her. She could sit outside as late as she wanted,” Amore says, implying that she was protected.

That’s Raymond Patriarca Sr., head of the New England Mafia from 1954 until his death in 1984.

Amore’s not boasting or being dramatic. He talks about the Mafia the way a person might talk about the weather.

“I’m not saying they were good guys, but this was in a time of ‘Stay out of their way and you’re fine,’” he says. “I’ve never been afraid of people, even the worst bad guys.

“When I first started investigating, I had this mentor, a retired Scotland Yard investigator, and one of the first lessons he taught me was that you have to be willing to speak to the devil,” Amore says. “And I go out looking for devils to speak to.”

“I have to have faith that I can recover these paintings.”

—Anthony Amore ’89

Amore’s mentor was legendary Scotland Yard detective Jurek “Rocky” Rokoszynski, who recovered two Turner paintings for the Tate Gallery in London between 2000 and 2002. Amore has also worked closely with the FBI Boston over his 20-year tenure, specifically former FBI agent Geoffrey Kelly, who himself investigated the Gardner heist for 22 years until April 2024, when he retired.

In his last week on the job, Kelly repatriated artifacts back to Okinawa, Japan, that had been looted in World War II. It was one of those situations where a relative was cleaning out a home after the death of a family member and, lo and behold, discovered stolen art.

Priceless and Worthless

Kelly and Amore’s investigation took them up and down the East Coast, chasing down leads about where the art might have gone. Both men believe the art is still in America, not in Japan, Ireland, Germany, or the many other places people have posited. It is highly unusual for an FBI agent to work with a civilian, but the bureau made an exception for Amore, at Kelly’s urging.

“I realized just what an asset he was to this investigation; I had somebody who was a really qualified, able investigator. We became partners in the investigation,” Kelly says.

“We received some credible information that a few pieces went up to Maine and a few pieces went down to Connecticut, and then maybe a few pieces might have gone to Philadelphia,” Kelly says. “We’ve had some very credible sightings of ‘The Storm’ over the years, and the Manet, too, but also some of the pieces nobody’s ever mentioned seeing.

“So, my gut says that this collection was split up sometime after the theft,” Kelly says. “It would be wonderful to think all 13 pieces are in one big shipping container somewhere, but my guess is that they’ve probably been scattered to the wind. But I think there’s a good possibility that some of these pieces have been hidden somewhere.”

As in, somewhere close by. There’s precedent: Rembrandts stolen from Massachusetts museums have been stashed locally, sometimes in unusual places. One taken from the Worcester Art Museum in the spring of 1972 ended up at the Picillo Pig Farm in Coventry, R.I. And when Myles Connor stole Rembrandt’s “Young Girl in a Gold-Trimmed Cloak” from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 1975, he hid it under a friend’s mother-in-law’s bed. Connor successfully used the Rembrandt as a get-out-of-jail-free card for another crime.

Aside from Connor, there aren’t a lot of thieves routinely stealing priceless artwork, because you just can’t move masterpieces, Kelly says.

“Smaller thefts, more anonymous artwork, jewelry that can be melted down and its stones removed, yeah, that’s a huge trade,” Kelly says. “But when you’re talking about famous pieces of art, recognizable pieces of art, pieces that are part of an artist’s catalog, you steal it once and you don’t come back and do it again because you realize it’s not worth anything,” Kelly says. “I’ve been asked so many times about the Gardner work; the term that’s bandied about is ‘priceless,’ and that’s true.

“But I also like to say they’re worthless, because the pieces only have monetary value to one organization in the world, and that’s the Gardner. So, from an aesthetic standpoint, they’re priceless; from a monetary standpoint, they’re worthless.”

It Would Be Torture

The cost to the individuals at the center of this drama is great. In a 2015 interview with Boston Magazine, the Gardner’s former museum director, Anne Hawley, called the heist “a devastation. It was like being knifed in the heart, really, for all of us—and for the city.”

“You need to temper the passion that you have with the other things going on in your life, and it’s difficult to keep that at arm’s length,” Kelly says. “Many times, over the years, the case has gotten too close, and it’s the same for Anthony. It’s difficult not to get a little obsessed with a case when you know it so well, when you’re so attached to it.”

Amore recalls a conversation he had with Hawley in which he shared that he intended to meet with a notorious Boston criminal to discuss the Gardner Museum case. According to Amore, the conversation went like this:

Hawley: “Are you sure you want to do this meeting?”

Amore: “Absolutely.”

Hawley: “Your life is not worth these paintings.”

Amore: “Yes, it is. The paintings are supposed to live forever. They’re supposed to be there for my children and my grandchildren and everyone else’s, too. They’ve been around for 300 years and there are still things to be learned from them. So, yeah. It’s worth my life.”

The thieves spent nearly 90 minutes in the Gardner Museum on the night of the heist. This is an unusually long time. As mentioned, most art thieves prefer the middle-of-the-day, smash-and-grab approach. Over the years, Amore has tried to recreate as closely as possible the events of the evening, including once having been in the museum at 1:24 a.m., the time of the theft. Amore’s walked in the footsteps of the two perpetrators and sat where the two young guards were held, restrained, in the basement.

“I’ve sat in the dark and pictured them walking,” Amore says. “I’ve pictured these guys moving around in their police uniforms. They weren’t rushing. They were comfortable here.”

Anthony Amore ’89 in the Gardner Museum’s iconic courtyard, located in the center of the museum and visible from most of the galleries.

They were also peculiar for what they didn’t take. Other paintings in the room were also valued in the tens of millions of dollars.

“So, they left behind a huge amount of money,” Amore says. “Right there, that tells you they’re not art connoisseurs.”

When she was making the Last Seen podcast, Horan says it wasn’t unusual for Amore to reach out late at night with the name of a person she should talk to or something she should look into.

“And I thought, ‘My God, is he ever not working on this?’” Horan says. “How many investigators are actually occupying the scene of the crime, actually living in the scene of the crime in the majority of their waking hours?

“I think it would be a torture to have to walk by those empty frames every single day,” Horan adds. “For me, it would be a torture.”

In March, a filmmaker staged the recovery of a fake “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee” at a Brooklyn gallery to promote his upcoming film. The video went viral on TikTok and Instagram. Such antics are more than salt in the wound for Amore. He was inundated with emails, calls, and texts that took up the better part of a weekend to answer. Kelly had sympathy for his friend and contempt for the filmmaker.

“This is artwork, not a human being, but to a lot of people in this world, especially people at the museum, that artwork is special. There are people out there who really want to see this artwork recovered.”

Isabella Stewart Gardner often visits Amore in his dreams—not in a woo-woo way but in the way a thing that dominates your daily thoughts tends to creep into your subconscious. In his dreams, Gardner is consistent both in her message and in her general appearance. Amore shares a sepia-toned digital image of Gardner in a black feathered hat and a dark moiré silk bodice. She is looking across her shoulder at the camera, her face wearing an appraising expression just shy of judgment. Think of Almira Gulch, the Wicked Witch of the West’s counterpart in The Wizard of Oz. The way her face is set. It’s that kind of vibe.

“Mrs. Gardner asks me why I haven’t found the paintings yet,” Amore says. “She’s urging me, not in a chastising way, but urging me, saying, ‘You have to find these. When are you going to find these?’ I very clearly see her asking me about them.”

In April, Amore interviewed Gardner’s biographer, Natalie Dykstra, at the Harvard Club of Boston. Dykstra wrote the 2024 national bestseller, Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Amore asked Dykstra what she thought Gardner might think of his 20-year quest to restore the stolen artwork.

Dykstra replied, “It was said of Mrs. Gardner that she annihilated the thought and possibility of failure.”

“Talk about inspiring,” Amore says.

This Is Command Central

The least impressive space in the Gardner Museum might be Amore’s office. The former bedroom of Gardner’s maid, the narrow, cramped space seems far too small for Amore’s 6-foot-2 frame. Amore had a bigger office elsewhere in the museum, but he wanted to be closer to the art. The room holds a desk, a computer, a chair, a set of shelves, and not much else. Put two adults in the space and it’s claustrophobic.

Behind his computer screen, dominating the wall upon which it’s mounted, is a reprint of “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” maybe 2 feet from Amore’s face. Some days, hope doesn’t come easily for Amore. Some days, “The Storm” evokes feelings of failure.

The Roman Catholic Church ascribes certain characteristics to its saints. St. Peter is the patron saint of fishermen. St. Teresa of Avila is the patron saint of the sick.

Amore’s namesake, St. Anthony, is the patron saint of lost things.

“I did an interview with a podcaster yesterday, and it’s funny because these people who interview me will introduce me saying that I’m the guy looking for these paintings,” Amore says, “and not five minutes later they’ll say, ‘Do you think they’ll ever find them?’”

“Who’s they?” Amore asks.

“I’m gonna find them.”

PHOTOS: SETH JACOBSON

Latest All News

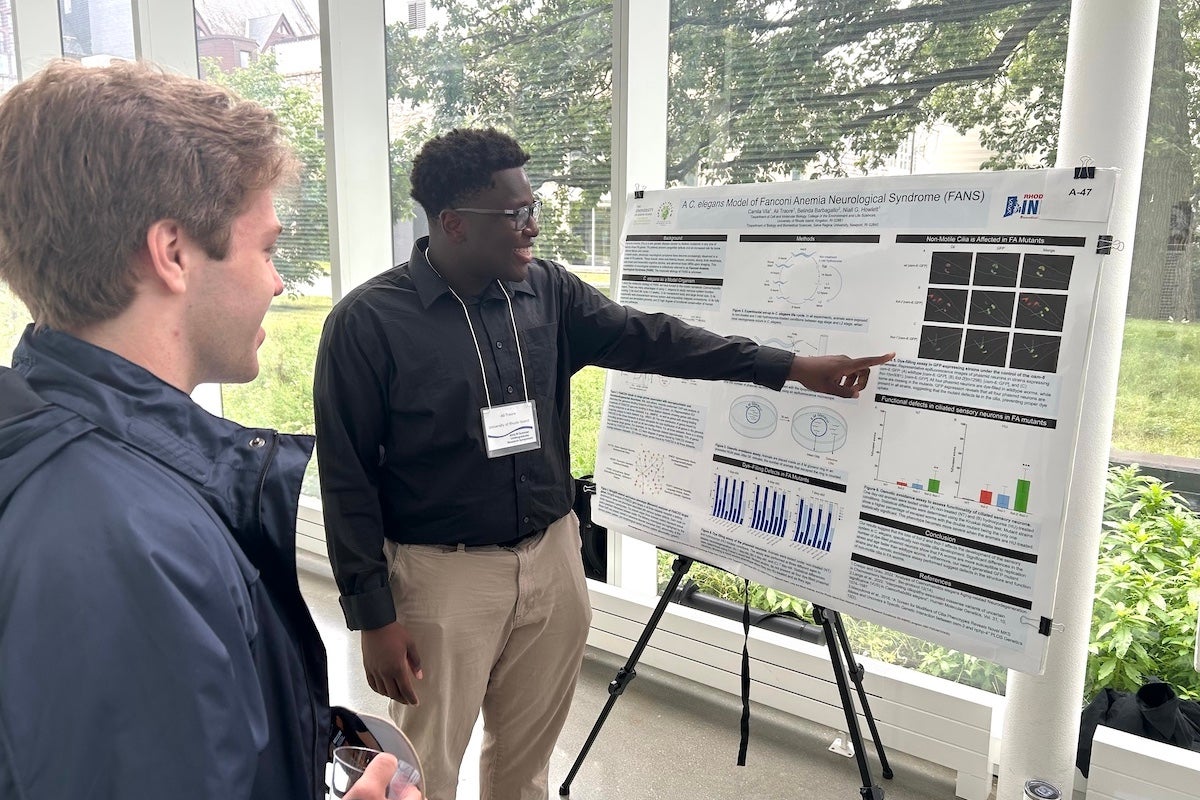

- Student researchers present dynamic biomedical studies during Summer Research SymposiumKINGSTON, R.I. — Aug. 7, 2025 — More than 350 students and faculty members from 10 colleges and universities around the state converged on the University of Rhode Island Aug. 1 to showcase 150 biomedical research projects they’ve spent the summer studying, as RI-INBRE, RI-EPSCoR-NEST, and Navy STEM hosted URI’s 21st annual Summer Research Symposium. […]

- URI Magazine Summer 2025Learn about a film bringing a mythic local tradition to life, URI's land-grant university mission, the mystery behind Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum's famed art heist—and much more.

- The Pickleball WavePickleball is America’s fastest growing sport; URI alumni, students, and faculty are riding the wave, too.

- A Debt to History – Why URI’s Land-Grant Mission Still MattersIt’s the “Why” of what we do at URI–ensuring research serves and positively impacts Rhode Island communities.

- More Than Hoops – An American StoryEvan Villari ’02 and Len Cabral are working on a film that will tell the story of the legendary North Providence Summer Basketball League.

- From the EditorThere’s been a big change here at URI Magazine since the last issue. Nora Lewis, who served as URI photographer for 33 years, retired.