A Debt to History – Why URI’s Land-Grant Mission Still Matters

Summer farm crew members at the Greene H. Gardner Crops Research Center on URI’s Kingston Campus. From left, Grace Connolly ’26, wildlife and conservation biology major; Aislin Aylward ’26, environmental science and management major and a Cooperative Extension agriculture and food systems fellow; Tricia Lourenco Boucher ’23, program facilitator for URI’s Boots to Bushels program, with her dog, Rosie; and Grace Chasanoff ’25, animal science major.

The University of Rhode Island embodies the three-pronged land-grant mission of education, research, and outreach—all with a focus on practical service to the state. Today, 163 years after the Morrill Act established land-grant universities—funded by the sale of land taken from Indigenous tribal nations—there is growing recognition that the origin story of land-grant schools is complicated. So, what does it mean to be a land-grant university today? And why does it matter?

By Anna Vaccaro Gray ’12, M.S. ’16

Black bean burgers with honey-cilantro-yogurt sauce are on the menu. The school day is long over, but a welcoming aroma drifts through Arlington Elementary School in Cranston, R.I. In the cafeteria, a group of children is busy mixing ingredients for the patties. As they add chopped red pepper, one child says, “These will help our hearts!” His announcement echoes the lesson just covered with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) staff.

In a nearby room, the children’s parents are talking about nutrition with SNAP-Ed staff, as well, about how to get more fruits and vegetables into meals. The conversation ranges from picky eating to culturally relevant recipe tips and is punctuated by empathetic sighs and uproarious laughter. When the burgers are ready, the parents join their children in the cafeteria for dinner together.

Twenty-seven miles from the Kingston Campus, this program exists because of URI’s land-grant mission.

What Is a Land-Grant University?

Before land-grant universities were established, colleges were considered elite and largely excluded working-class people. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Land-Grant College Act in 1862, it was a reckoning for higher education’s civic purpose; It was the birth of public universities in the United States.

The objective of the Morrill Act was to make higher education accessible to a broader population and to ensure that it delivered a practical curriculum. Specifically, land-grant colleges were created to teach agriculture and mechanical arts (what we call engineering today), as well as classical studies (liberal arts).

Making education more accessible and practical was a noble idea with many merits, but the undertaking was flawed in many ways, including the unjust and violent means by which it was financed. The Morrill Act granted land in the western U.S. to colleges and universities, which, in turn, sold the land and used the proceeds to fund programs in agriculture and mechanical arts. The land granted to schools by the Morrill Act was land seized by the federal government from Native tribes.

Today, the complexity of the land-grant system’s origins shapes how the University of Rhode Island pursues the land-grant mission of practical education, research, and outreach. A variety of disciplines, from nutrition and education to the humanities, focus on serving communities statewide with practical knowledge and training. URI is acknowledging the land-grant system’s past and working collaboratively and meaningfully with communities to improve and enrich life in the Ocean State.

Staying Focused on Farms: URI’s Agricultural Experiment Station

In 1887, the Hatch Act established Agricultural Experiment Stations at land-grant schools. These research centers focused on improving food production and agribusiness. They became—and continue to be—important components of land-grant schools.

Rhode Island has about 59,076 acres of farmland, according to the 2024 Census of Agriculture. The land-grant system’s focus on agriculture has helped protect Rhode Island farmland throughout the years, according to Rebecca Brown, URI professor of plant sciences and entomology. This matters, she says, because “when farms aren’t seen as important, they become building sites.”

Today, URI’s Agricultural Experiment Station includes three farms and several greenhouses on the Kingston Campus and at East Farm. The Greene H. Gardner Crops Research Center, also called Agronomy Farm, hosts research and teaching plots as well as 4 acres used to grow produce for URI Dining Services, the Free Farmers Market, and Rhody Outpost, a food pantry for students. East Farm is used for research in aquaculture, ornithology, entomology, wildlife habitats, and more. Peckham Farm is home to URI’s animal science program, a variety of livestock used for teaching and research, and 18 acres of hayfields and pastures.

“It’s gratifying to see students find jobs in agriculture and to see farmers stay in business.”

—Rebecca Brown, URI Professor of Plant Sciences and Entomology

“We have a mission to teach and support agriculture across the state,” says Brown. Her department is part of a network that supports farmers and works with the state government to ensure food regulations are grounded in science.

The land-grant system’s historical and ongoing support of agriculture is also good for the economy. According to the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, recent data indicates that for every $1 in public investment, food and agriculture research and development from land grants has returned $20 to the American economy. Brown has witnessed this firsthand. “It’s gratifying to see students find jobs in agriculture and to see farmers stay in business.”

Rebecca Brown, URI professor of plant sciences and entomology, at the Greene H. Gardner Crops Research Center on the Kingston Campus. On the tractor is summer farm crew member and animal science major Simon Tetreault ’25.

Brown works closely with David Weisberger, an agricultural extension agent for URI’s Cooperative Extension, who meets regularly with farmers, nonprofits, and state agencies, like the Division of Environmental Management and the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Rhode Island. “What I find most worthwhile about working for a land-grant institution is being a civil servant for the farmers of Rhode Island,” Weisberger says. “Industries can play an important role, but because we are public sector workers, we aren’t selling anything. We’re just sharing information and feedback with farmers to help them solve problems.”

Weisberger and Keiddy Urrea-Morawicki, director of the URI Plant Diagnostic Laboratory, provide workshops on pest and soil management for the Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) in Providence, R.I., which oversees 21 community gardens in Providence, Pawtucket, and Central Falls. Last winter, SCLT participants had questions about how to successfully grow two tropical vegetables—okra and African eggplant (also known as bitter ball), a staple in West African cuisine. Brown is now conducting research trials on how to adapt these crops for Rhode Island soil. “We want to help SCLT members learn ways to grow these crops that yield more harvest by changing production practices and the varieties they grow,” she says.

Cooperative Extension, Then and Now

Unique to the land-grant mission is the focus on extension, or research-backed service, that actively contributes to improving the state. Kenyon Butterfield, URI’s shortest-serving president from 1903 to 1906, felt strongly about this pursuit and organized an extension department in 1904—a decade before other land-grant colleges. He employed agents to liaise between the school and the public, disseminating information gleaned from research while keeping a finger on the pulse of people’s needs.

In 1914, Butterfield’s system was formalized when the Smith-Lever Act created a system of Cooperative Extension programs at land-grant universities nationwide. As society’s needs changed, Cooperative Extensions proved their relevance. During World War I and the Great Depression, they were anchors in a sea of social and economic turmoil, helping people with, among other things, learning about food production and preservation.

“Extension agents taught people about food canning, gardening, home poultry production, and other practical skills that helped families survive,” says Michael A. Rice, URI professor of fisheries, animal, and veterinary sciences. “They were trusted because their recommendations were, and still are, based on science.”

Since its inception, URI’s Cooperative Extension has been an important bridge between the University and the public. Active in all 39 municipalities in Rhode Island, URI’s Cooperative Extension operates through the

College of the Environment and Life Sciences.

Cooperative Extension faculty and staff partner with state and local agencies to address environmental, social, and economic concerns. The scope is extensive: from the Aquaculture Extension program, which connects the state’s aquaculture producers to science-based, sustainable, and profitable aquaculture practices, to the Onsite Wastewater Resource Center, which provides education on best practices for protecting water quality and public health and encourages sustainable development.

“Our mission is to ensure that URI research will help our communities,” says Lisa Townson, associate dean for extension and agriculture programs. “We are here to provide helpful information based on science, but we also listen to people’s problems, and that goes into developing our research questions.”

“We’re providing data that helps communities make good decisions that lead to quality of life and a strong economy in the state,” Townson adds.

Cooperative Extension programs deliver impressive results. Last year, the Food Recovery for Rhode Island program gleaned and rescued 231,785 pounds of food, which was donated to feed Rhode Islanders, and diverted an additional 8,196 pounds of food from the landfill; volunteers with the URI Watershed Watch program regularly monitored 220 fresh and marine water bodies; and the Plant Diagnostic Laboratory identified more than 500 plant, insect, and disease samples.

Nutrition: Community Impact Has State Impact

Sarah Amin, associate professor of nutrition, came to URI because the land-grant mission allows her to focus on the community impact of her work. “Research often has to prioritize funding over community needs,” she says. “Because land-grant mission work is meant to meet the needs of the community, I let the community lead my research.”

Amin is the director of Rhode Island’s SNAP-Ed and Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP), complementary federal programs that address food insecurity and nutrition disparities by providing nutrition education to low-income individuals and families. Like Cooperative Extension’s World War I-era programming that taught people how to preserve food, programs like SNAP-Ed and EFNEP identify community nutrition needs and address them with practical, research-based solutions.

“Because land-grant mission work is meant to meet the needs of the community, I let the community lead my research.”

—Sarah Amin, URI Associate Professor of Nutrition and Director of Rhode Island’s SNAP-Ed and EFNEP programs

Amin’s team conducts programming on nutrition literacy, cooking skills, food safety, and making healthier food choices on a limited budget. “SNAP-Ed and EFNEP educators foster self-sufficiency so that individuals can advocate for themselves around food choices,” Amin says. “The communities we work with are resilient, but due to structural inequities, often lack resources to make healthier choices.”

While Amin is based in URI’s nutrition department, her team is not on campus. “Being physically located in the Providence area is important for us because that’s where the communities we serve live, shop, work, and play,” she says. “We’re not just going in, running a program, and leaving. We’re constantly assessing needs, interests, and perceptions about the programs we provide.”

A SNAP-Ed program at Arlington Elementary School in Cranston, R.I., engages children and their parents in practical nutrition education, like how to get more fruits and vegetables into meals.

Meeting people where they are and providing services without an agenda, she says, builds something invaluable: trust.

Over 100 partners—including schools, food pantries, farmers markets, public housing sites, and more—work with SNAP-Ed and EFNEP to reach underserved populations through programs like the one at Arlington Elementary School. “We’re really lucky to work with URI,” says Sarah Blau, state nutrition coordinator for the R.I. Department of Health’s Healthy Eating and Active Living program. “They have been a critical partner.”

Rhode Island’s small area has advantages, both Amin and Blau note: It’s easy to be connected to all the players in the food system. “It’s such a small state that we can impact a community and have state-level impact,” Amin says.

Science Education: Working Symbiotically

Sara Sweetman, Ph.D. ’13, URI associate professor of education, directs the Guiding Education in Math and Science Network (GEMS-Net), a program that advances science education by helping Rhode Island teachers implement innovative science curricula developed by researchers. The program aligns with the land-grant mission of extending knowledge and resources to the public. “URI is a public institution working with public schools in a symbiotic way,” she says.

GEMS-Net brings teachers and administrators from 13 public school districts together with URI researchers and educators for workshops, professional development, and mentoring. The programming often takes place in the schools. “When I’m in a school, I always eat lunch with teachers,” Sweetman says. “It’s the best place to hear about the challenges in education, what’s happening in classrooms, and the latest trends that should be put into research.”

URI education professor Sara Sweetman, Ph.D. ’13, works with science teachers in a GEMS-Net workshop.

“Research is only important if it’s useful; we need it to be translatable.”

—Sara Sweetman, Ph.D. ’13, URI associate professor of education

Sweetman’s research informs—and is informed by—her interactions with teachers in the GEMS-Net program. Her research areas include children and climate change, research practice partnerships, teaching science through media, outdoor education, and the intersection of enjoyment and learning.

“Research is only important if it’s useful,” she adds. “We need it to be translatable.”

GEMS-Net also offers leadership opportunities for public school teachers, which is unusual in the profession. Christina Broomfield ’09 has made use of those opportunities.

An elementary school teacher in North Kingstown, R.I., Broomfield attended GEMS-Net workshops early in her career. “I appreciated that it was the same team of workshop facilitators every time, and not a company sponsoring the curriculum,” she says. “It also felt like our time as educators was valued.” She started facilitating workshops and later became a teacher-in-residence for GEMS-Net.

Christina Broomfield ’09, an elementary school teacher in North Kingstown, R.I., says that her participation in GEMS-Net has made science her strongest teaching area.

“GEMS-Net has been a constant in my career, I know I’m always going to get support from the team. It makes me feel really empowered.”

—Christina Broomfield ’09

As GEMS-Net staff copresent workshops with teachers and researchers, Broomfield says she appreciates the emphasis on collaborative expertise. “I refer to the teachers as the street cred,” she says. “They add that realistic piece of what the activity will look like in action.”

Elementary school educators are responsible for teaching all of the core subjects in their classrooms. Science is Broomfield’s strongest area, she says, because of the instruction and professional development she’s received from GEMS-Net. The ongoing support helps, too. “GEMS-Net has been a constant in my career,” she says. “I know I’m always going to get support from the team. It makes me feel really empowered.”

Liberal Arts: Ethical and Engaged Work

One of the architects of the 1862 Morrill Act, Jonathan Baldwin Turner, wrote that the land-grant system was meant to “extend the boundaries of our present knowledge.” The liberal arts are a necessary component of that pursuit. While applied scientific research produces measurable impact, the liberal arts fortify land-grant work. URI faculty who work between disciplines exemplify the power of this approach.

Cheryl Foster, URI professor of philosophy and political science, specializes in environmental philosophy and often works with policymakers and scientists to develop surveys and run community dialogue groups. She recalls a project she worked on early in her career that involved understanding local resistance to an aquaculture proposal. The scientists were focused on cultivating a sustainable food source, but there was resistance from community members who worried about the consequences for their property values and sight lines.

“You can’t address that resistance entirely from within applied science. You have to consider ethical and aesthetic dilemmas, and seek to understand people’s values by listening closely, sometimes for things that sit beneath what folks are saying directly,” she says. The liberal arts teach us how to understand people and communities and solve conflicts. “That’s where the liberal learning piece comes in,” she adds.

Madison Jones, URI assistant professor of professional and public writing and natural resources science, sits formally between two worlds: liberal arts and applied sciences. “Humanists do land-grant mission work in a way that has typically gone unseen or unacknowledged because it isn’t necessarily a product,” he says. “But we need the humanist perspective to ask: Why are we doing this? What is it going to do for humans? How is it going to affect our democracy?”

“One of the most important things we can do to respond to the world we’re living in is to foster interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary work,” he adds. “It can be an exhausting approach, but it’s a rewarding one, and it brings us toward more ethical and engaged work.”

Cheryl Foster, URI professor of philosophy and political science, and Madison Jones, URI assistant professor of professional and public writing and natural resources science, say the liberal arts perspective helps researchers understand the people and communities they serve.

Jones founded the DWELL (Digital Writing Environments, Location, and Localization) Lab at URI to advance innovative approaches to science communication. The lab considers how humans interact with places through deep mapping, which layers media and information to represent not only a place’s physical characteristics, but also its history, the lived experiences of its inhabitants, and more.

One of DWELL’s project sites is North Woods, a 300-acre parcel of unmanaged forests and wetlands next to URI’s Kingston Campus. Jones’ team created an interactive experience about the relationship between URI and the land it uses. They worked with an artist from the Narragansett Indian Tribe to create a walking tour of North Woods based on a traditional Narragansett ecological story about how birds got their song.

“Taking a geological view and layering in cultural, historical, and ecological information allows different stories to inhabit the same space at the same time, even if those stories are in conflict with one another,” he says.

An Invitation to Respond

The land-grant system epitomizes a fundamental contradiction. “The ‘public good’ [that land-grant] institutions purported to promote was only possible because of violence and dispossession of ancestral Indigenous land, and acknowledging this dissonance is important for true understanding,” wrote URI student Jenny Sullivan ’21, M.A. ’24, in her master’s thesis, “Origins and Consequences of Rhode Island’s Land-Grant Institutions.”

Confronting this history and the changes to higher education and society that came from it is, according to Jones, something that “compels and invites our response.” Essential to our response are the values at the core of the land-grant mission itself: working and collaborating meaningfully with communities to improve and enrich our shared reality.

The complexity of the land-grant system’s history, not unique to URI, is not lost on faculty engaged in land-grant work; rather, it fuels their desire to contribute to the public good through equitable, engaged work.

“In my experience, people at URI are willing to ask questions and to learn,” says Dinalyn Spears ’95, director of community planning and natural resources for the Narragansett Indian Tribe. “They want to be educated about our history, and they are proactive in working with the Tribe.”

Spears teaches Indigenous uses of native plants and the Narragansett Indian Tribe’s food sovereignty efforts in URI Cooperative Extension’s Master Gardener program, which trains and certifies people to become community educators who teach Rhode Islanders about environmentally sound gardening practices. Spears completed her Master Gardener training in 2015. She has a farm in Westerly, R.I., where she grows vegetables and medicinal and culinary herbs for tribal citizens.

Dinalyn Spears ’95 is director of community planning and natural resources for the Narragansett Indian Tribe and a URI Master Gardener. Spears serves as an instructor for the Master Gardener program, offering traditional ecological knowledge around the indigenous uses of native plants. URI Master Gardener program leader Vanessa Venturini ’08, M.E.S.M. ’11, calls Spears “a true community leader, a respected elder in the community, and a connector to URI Cooperative Extension, where she now sits on our advisory board.” Spears is pictured (left) with fellow Master Gardener Maria Rivera-Saillant.

Spears notes that at URI, there are growing efforts toward achieving a more fully realized version of the accessibility and inclusivity promised by the original land-grant legislation. A scholarship was established for undergraduate students who are citizens of the Narragansett Nation. URI’s land acknowledgement, a public statement recognizing that the University occupies the land of the Narragansett Nation and the Niantic People, was written in collaboration with John Brown, the Narragansett Indian Tribe’s tribal historic preservation officer. And the Tomaquag Museum, one of the oldest tribal museums in the country, is slated for a new location on URI’s Kingston Campus.

While there is more that can and should be done, Spears points to these examples as emblematic of the current climate. “The past is important,” she says, “but there is a time to come together, move forward, and build new relationships.”

The complexity of the land-grant system’s history, not unique to URI, is not lost on faculty engaged in land-grant work; rather, it fuels their desire to contribute to the public good through equitable, engaged work.

Being part of a land-grant university carries with it a debt born of a complicated history. “It’s a debt,” Jones says “that we owe to taxpayers in the state, to the communities that call Rhode Island home, and to each other. It’s an obligation and an exigency.”

PHOTOS: COURTESY URI SNAP-ED PROGRAM; COURTESY URI MASTER GARDENER’S PROGRAM; SETH JACOBSON, NORA LEWIS

Author’s Note

In addition to being a land-grant institution, URI became a sea-grant school in 1972 and an urban-grant school in 1995. Modeled after the land-grant system, sea-grant schools focus on the sustainable development of marine and coastal resources, balancing conservation with economic and community interests. Urban-grant schools focus on serving urban communities and ensuring that education, research, and outreach are accessible to people living in urban communities.

The full scope of incredible land-, sea-, and urban-grant work being done at URI could not be captured in this story, but I hope that it inspires you to think about and learn more about the land-grant mission. I also hope that it sparks ongoing conversations about how we can all contribute to strengthening our communities.

—Anna Vaccaro Gray

Learn more about the history and current state of land-grant institutions, including URI:

Land-grant university FAQ

www.aplu.org/about-us/history-of-aplu/what-is-a-land-grant-university/

From the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities

A history of URI

www.uri.edu/about/history/detailed-history/

A Walk Through Time

www.uri.edu/features/a-walk-through-time/

An interdisciplinary URI team offers a broader history of URI with the Walk Through Time

course.

Origins and consequences of Rhode Island’s land-grant institutions

digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/2480/

A master’s thesis by Jenny Sullivan ’21, M.A. ’24

Rhode Island’s contributions to nationwide land-and-sea grant extensions

www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael-Rice-

9/publication/269633531_Philosophical_Institutional_Innovations_of_Kenyon_Leech_B

utterfield_and_the_Rhode_Island_Contributions_to_the_Development_of_Land_Grant_

and_Sea_Grant_Extension/

An academic paper by Michael Rice, URI professor of aquaculture and fisheries and

chair of the Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Sciences Department at URI; Salina

Rodrigues, M.L.I.S. ’00; and Kate Venturini ’06, M.A. ’10

The Land Back movement in the United States

storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/5801514a54dc48028e20b0b97183c082

A master’s project by Lindsay Brubaker, M.A. ’24

Land-Grab Universities: A High Country News Investigation

www.landgrabu.org/

Latest All News

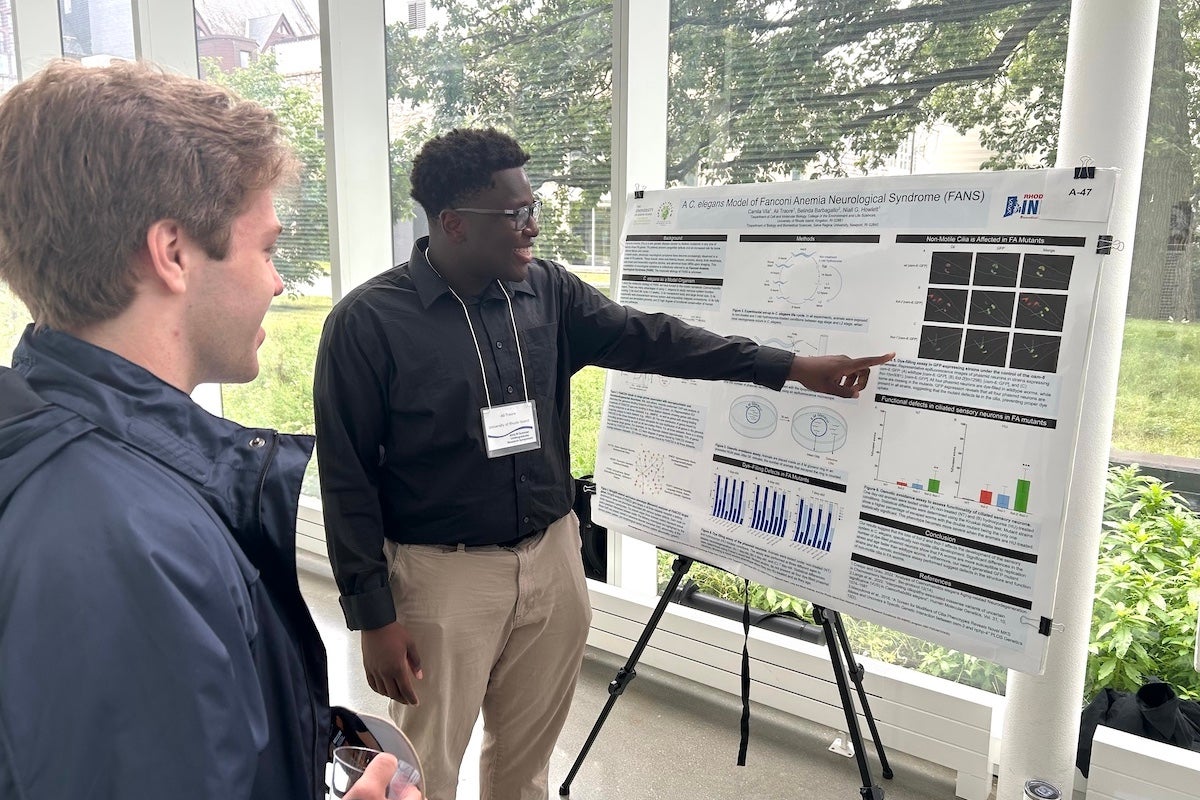

- Student researchers present dynamic biomedical studies during Summer Research SymposiumKINGSTON, R.I. — Aug. 7, 2025 — More than 350 students and faculty members from 10 colleges and universities around the state converged on the University of Rhode Island Aug. 1 to showcase 150 biomedical research projects they’ve spent the summer studying, as RI-INBRE, RI-EPSCoR-NEST, and Navy STEM hosted URI’s 21st annual Summer Research Symposium. […]

- URI Magazine Summer 2025Learn about a film bringing a mythic local tradition to life, URI's land-grant university mission, the mystery behind Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum's famed art heist—and much more.

- The Pickleball WavePickleball is America’s fastest growing sport; URI alumni, students, and faculty are riding the wave, too.

- More Than Hoops – An American StoryEvan Villari ’02 and Len Cabral are working on a film that will tell the story of the legendary North Providence Summer Basketball League.

- Chasing the Storm2025 marks the 35th anniversary of the largest art heist in history. Anthony Amore ’89 has spent 20 years searching for the stolen art—and he’s more determined than ever to find it.

- From the EditorThere’s been a big change here at URI Magazine since the last issue. Nora Lewis, who served as URI photographer for 33 years, retired.