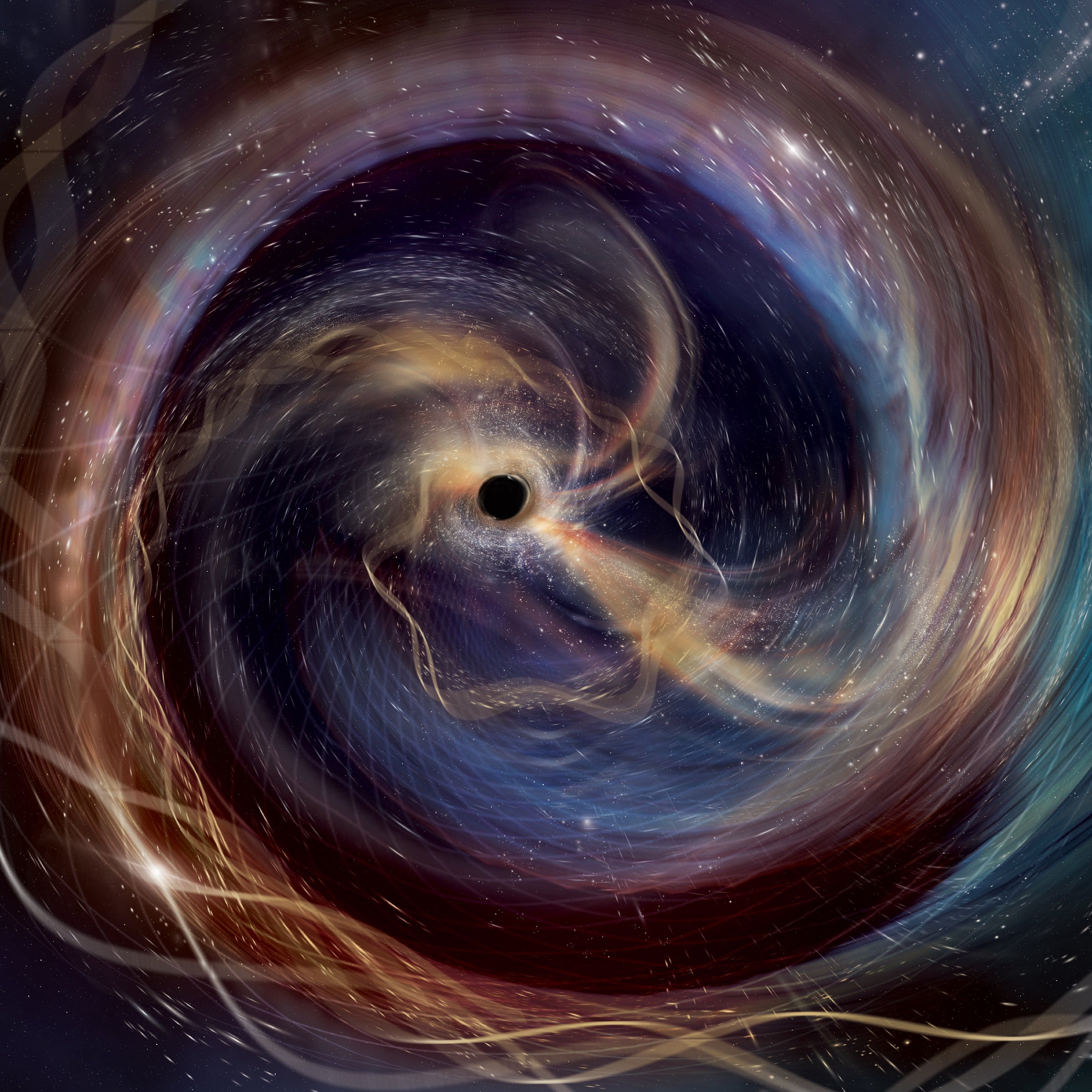

URI Gravity Research group contributes to major black hole discovery, expands astrophysics program

KINGSTON, R.I. – Oct. 6, 2025 – In 1915, Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity predicted that black hole collisions could only be detected from Earth by searching for gravitational waves. In September 2015, about a century after Einstein’s prediction, black holes were observed merging for the first time by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

A decade after the first gravitational wave was detected, LIGO has announced that a few hundred gravitational wave signals were recently identified. This significant discovery, which includes work by physics researchers at the University of Rhode Island, was recently featured by CNN.

“We’ve seen one signal every three days when it took us about 100 years to see the very first one,” URI assistant physics professor and Simons Foundation scientific software research faculty fellow Derek Davis said. “In the same way that gravitational astronomy has sprouted out and now has become this really big field, I feel the URI gravity group is doing the same thing.”

LIGO researcher Rob Coyne joined the University’s physics department in 2017, becoming the first gravitational wave researcher at URI at that time. Coyne formed the URI/UMass Gravity

Research Consortium (U2GRC) in 2021, along with URI professor Gaurav Khanna and University of Massachusetts Dartmouth professor Scott Field.

U2GRC focuses on research areas such as black holes, gravitational waves, multi-messenger astronomy, astrophysics, and quantum gravitation.

Now, URI’s physics department has more than 20 students and faculty studying astrophysics, and a vision to further grow the program with plans to introduce an astrophysics major for undergraduate students.

The major will be available to all current first- and second-year students as well as incoming students. U2GRC currently supervises more than half of the physics department’s six to 12 annual senior capstone projects.

“This idea of collaborating with students, other faculty, other researchers across the world is something that is really in our science culture,” Davis said. “Not only do we need to do it, but we’re all excited about it.”

URI’s astrophysics program prioritizes student engagement, focusing strictly on research work, which is an unconventional approach taken within academia. The high-impact, research-active departments in STEM at other institutions follow the stock standard in which faculty teach less and research more. Engaging students through research was essential for URI’s physics department to achieve this ethos.

Khanna joined URI as the director of research computing in 2021 and is now assistant vice president. The astrophysics team, along with Davis, Field, Khanna and Coyne, consists of Michael Pürrer, URI computational scientist and adjunct assistant professor of physics; Jaewoong Jung, research faculty member on a NASA grant; Aidan Chatwin-Davies, joint member of the quantum and astrophysics groups at URI; Deborah Ferguson, URI assistant professor; and Doug Gobeille, URI teaching professor.

“Each of us has succeeded in securing Rhode Island space grant funding, National Science Foundation grants, as well as NASA funding, including guest observer opportunities,” Coyne said. “We’re looking at high-performance computing grants through the new Institute for AI & Computational Research that Khanna has set up and we’re targeting both small- and mid-scale National Science Foundation grants, including grants that focus on AI research and education. You name it, we’re trying to do it.”

The department is also aiming to contribute to a new, larger gravitational wave observatory for students and faculty at URI.

“In the United States, the new project that’s being funded is Cosmic Explorer. It has approximately 40-kilometer-long arms, compared to LIGO’’s 4-kilometer-long arms,” Davis said. “This is a really fantastic time to get involved because we have the opportunity for faculty, researchers, and students to make contributions that will contribute to the direction of the field for literally decades.”

As the program expands, more opportunities for students to get involved in research, workshops, and more, will develop at URI. Coyne says the group is looking to increase its ties to the LIGO Scientific Collaboration as they continue to try to evolve the global international network of gravitational wave observatories with Virgo and KAGRA – which partnered with LIGO on the black hole wave discovery.

The faculty accesses some of the world’s best supercomputers and encourages students to learn how to be scientists in the “big data” era. Faculty members are also looking to be an integral part of the supply chain and are seeking young, bright scientific minds to contribute to improvements for the next observational run.

This also includes regional meetings such as the Northeast Regional Quasi-Stellar Radio Source (QUASAR) meeting, the Eastern Gravity meeting, and the New England American Physical Society meeting, along with national gatherings such as the American Astronomical Society meetings.

URI’s physics department looks forward to growing and serving on the cutting edge of astrophysics research. As an R1 institution, URI is poised for the possibility of unprecedented student contributions going forward.

“The original proposals for LIGO were in the 1980s. Now, we’re here in 2025. There’s really an opportunity for URI to be a big part of the next 50 years of gravitational wave astronomy,” Davis said.

Erin Malinn ’28, a University of Rhode Island journalism major, wrote this story.

Latest All News

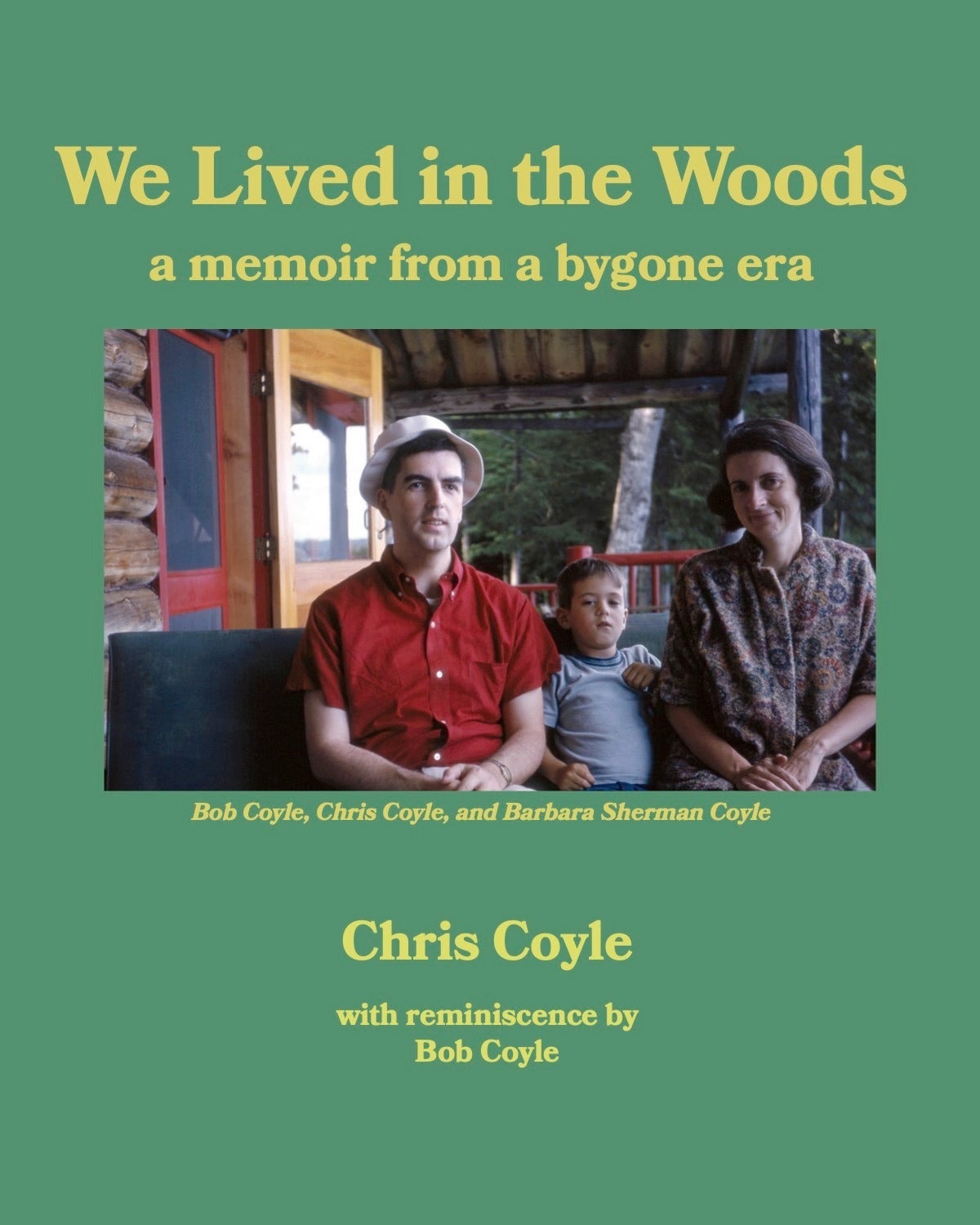

- We Lived in the Woods: A Memoir From a Bygone EraWe Lived in the Woods: A Memoir From a Bygone Era Alexander B. Blunt, M.A. ’11 (2025)

- After Rhode Island’s shoreline access law, what’s next?KINGSTON, R.I. – Oct. 8, 2025 – These recent sunny days bring the last chances to access the Rhode Island coastline before chillier weather sets in, though that won’t keep Jesse Reiblich away. When he’s not in or around the water — as an avid surfer, diver, and sailor — the University of Rhode Island […]

- What If? An 85 Year Journey of the Confederate States of AmericaWhat If? An 85 Year Journey of the Confederate States of America Arthur S. Bobrow ’64 (2025)

- Next URI Honors Colloquium lecture to ask, ‘What Can We Afford?’KINGSTON, R.I. – Oct. 7, 2025 – In today’s political environment, it’s critical to understand how public policy intersects with United States colleges and universities. Higher education policy expert Dominique J. Baker will discuss how education policy shapes access, equity, and success for minoritized students in higher education, as the University of Rhode Island continues […]

- URI professor examines use of technology to monitor patients after joint replacementKINGSTON, R.I. – Oct. 6, 2025 – Joint replacement surgery has advanced dramatically thanks to new materials, techniques, and technology. Procedures are safer, less invasive, and require less recovery time. While there have also been great advancements in technology used to remotely monitor how patients recover from joint replacement surgery, also known as arthroplasty. However, […]

- Applications due Oct. 24 for new environmental management fellowship programKINGSTON, R.I. — Oct. 6, 2025 — The University of Rhode Island Cooperative Extension is excited to announce the launch of the Environmental Management Fellows Program for students at URI and the Community College of Rhode Island. Cooperative Extension’s newest fellowship program builds on the success of URI’s popular and well-known Energy Fellows Program and […]