Caribbean coral reefs’ chronic decline could get a boost from proactive assisted gene flow — if allowed

KINGSTON, R.I. – July 30, 2025 – Coral reefs are under threat from warming oceans and prolonged heat — but regulatory inaction also poses a risk.

However, marine biologists say that new approaches in the region could help prevent species loss and retain ecosystem function, if they get the permission to proceed.

One approach that can benefit the reefs is assisted gene flow (AGF), a powerful tool to boost coral resilience. The approach was recently approved to help save elkhorn corals in Florida from local extinction but faces challenges in applying, due to static regulatory frameworks. The precautionary nature of such regulations, slow to change to environmental needs, poses a further threat to threatened corals.

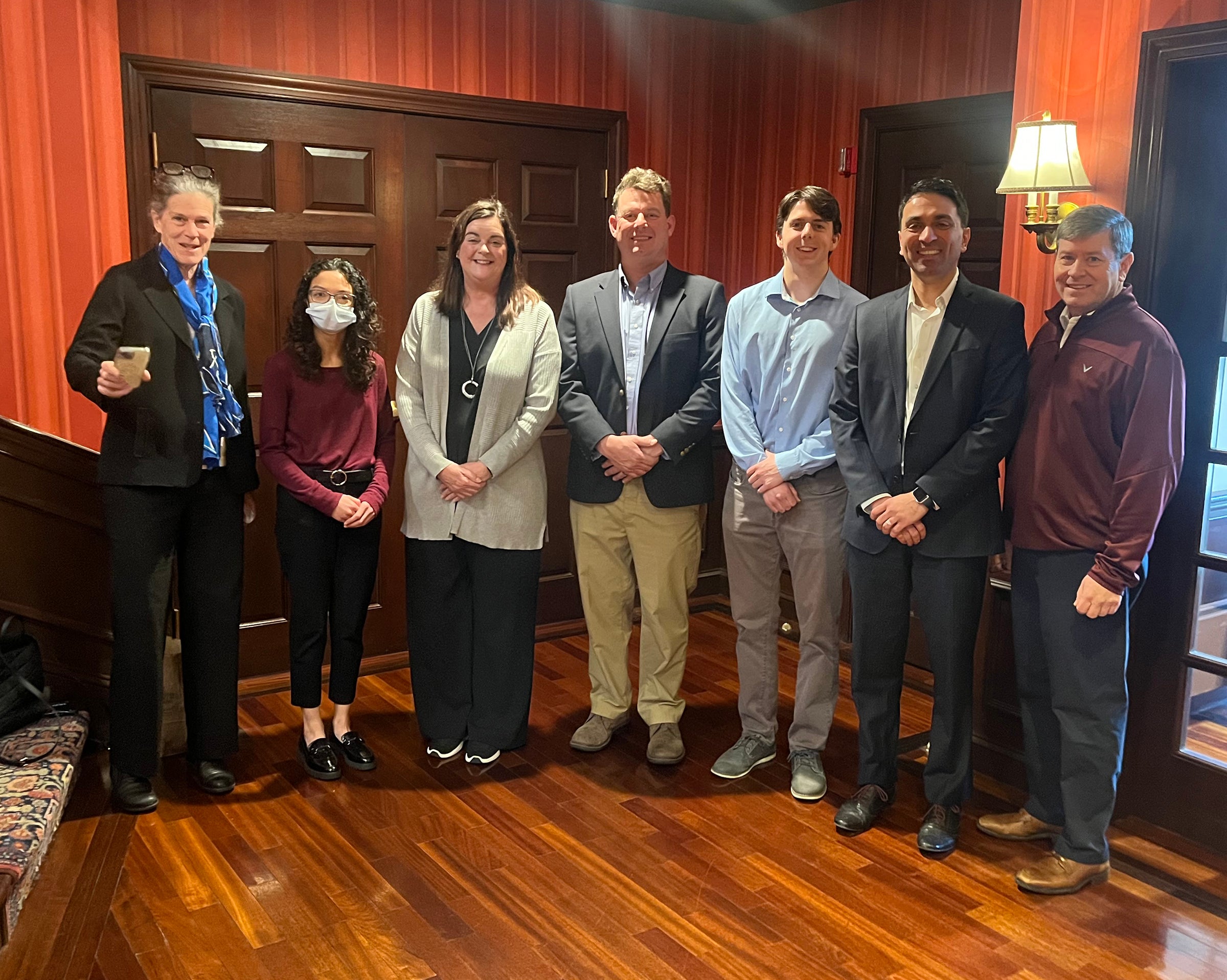

Carlos Prada, an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Rhode Island, recently co-authored an article in Science, addressing the policy aspects of coral restoration work and advocating for the use of assisted gene flow to provide corals in the region with the boost they need to survive.

Assisted gene flow involves introducing individuals, gametes, or alleles (via controlled crosses) to enhance the survival and reproductive success of species that have experienced severe declines, such as Caribbean corals. Though AGF has been applied in terrestrial ecosystems, it is still new in marine contexts. This managed interbreeding can boost genetic diversity and improve traits like resilience or disease resistance. Corals could be treated like other live plants, leveraging networks between nations to protect this regional natural resource.

Corals have been a focus of his research since Prada first studied them as an undergraduate marine biology major in Colombia. He says he still hasn’t found anything more fascinating than coral reef ecosystems. At URI, his work focuses on answering practical questions about how to preserve, protect and restore these unique organisms and other life found in the oceans.

Now, Prada is joined by 14 other international coral scientists, urging regulatory reform to accelerate global coral restoration using assisted gene flow, calling it an essential step to safeguard the economic value and coastal protection that reefs provide.

The intense marine heat wave of 2023 (with ocean temperatures above 30°C/86°F) illustrates the urgency of using AGF to help preserve genetic diversity in the region; protecting corals in advance of future mortality events would be a step in the right direction. But the clock is ticking.

Events like this used to occur every 10 years, then every five; however, the region experienced back-to-back marine heatwaves in 2023 and 2024. These increasingly frequent events are making it difficult for corals to recover.

The impact also extends up the Atlantic coast, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reporting declines in fish densities in the western Atlantic and an increase in algal blooms. In areas like Narragansett Bay, warmer conditions are also linked to harmful algal blooms, including red tides.

While there are some genetic risks associated with introducing diversity from outside a local population, Prada and other researchers suggest that unless steps are taken to introduce more adaptive genetic variants, the corals off the coast of Florida and in the Caribbean will likely disappear within a few decades.

The current rate of warming and the repeated occurrence of marine heatwaves indicate that further coral losses are a “not if, but when” scenario, underscoring the need for immediate action. Researchers say the window of opportunity for effective large-scale implementation of the technique is closing rapidly; waiting until genetic rescue is “needed” to save coral species on the brink of extinction may be too late.

Prada is part of the Coral Restoration Consortium, which advises restoration efforts and develops guidelines for practitioners and policymakers. The group meets monthly to address issues related to restoration and conservation. This topic has become a priority for them due to regulatory hesitation around AGF, he says.

“To properly evaluate assisted gene flow, agencies need to permit the necessary research — which is what we’re advocating for,” he says.

A few AGF trials involving corals were conducted in 2021 at Mote Marine Lab in Sarasota, Florida; however, due to regulatory restrictions that prevent the planting of corals in the wild, these efforts haven’t progressed beyond the lab. Prada says this limits scientists’ ability to assess the benefits of AGF in real-world reef environments. He and others in the consortium are advocating for such an approach to help save corals off the Florida coast that have been heavily impacted by human activity.

“We’re supporting this research because coral populations are at a tipping point, and the cost of inaction is growing rapidly,” Prada says.

Latest All News

- John Olerio named to Providence Business News 40 Under Forty listKINGSTON, R.I. – July 31, 2025 – University of Rhode Island Executive Director of Strategic Initiatives John Olerio M.B.A. ’11, Ph.D. ’20 has been recognized with a PBN 40 Under Forty Award by Providence Business News. The annual award recognizes individuals under the age of 40 who have excelled in their profession and are involved […]

- Core matters: URI geoscientist weighs in on critical mineralsKINGSTON, R.I. – July 31, 2025 – Critical minerals are a hot topic in the news these days, whether as a point of contention between countries or in discussions of supply and demand. Critical minerals are nonfuel minerals/metals necessary to industry and are essential in a wide range of technologies. Their availability is sensitive to […]

- URI jazz students to return to Newport Jazz Festival for third yearKINGSTON, R.I. – July 31, 2025 – University of Rhode Island music students will again take the stage at the legendary Newport Jazz Festival. Playing a half-hour set that tips the hat to the festival’s vast history, the seven URI students will perform Sunday, Aug. 3, at about 2:45 p.m. on the Foundation Stage at […]

- Navigating health careIf you’ve had to find a primary-care provider or pay a medical bill lately, you know that accessing and paying for health care can be difficult. But why? How can we get the care we need?

- URI Consulting Club helps Providence Mutual combat carbon emissions levelsKINGSTON, R.I. – July 29, 2025 – The University of Rhode Island continues to leave an indelible mark on its students—an influence that extends well beyond the Kingston Campus to prominent businesses such as Providence Mutual Fire Insurance Company. For Providence Mutual, that impact will be lasting, thanks to the work done by the URI […]

- URI to host RI-INBRE Summer Research Symposium Aug. 1KINGSTON, R.I. — July 29, 2025 — About 200 students from 10 institutions across Rhode Island will present more than 100 biomedical research projects they’ve spent the summer studying, as RI-INBRE hosts its 21st annual Summer Undergraduate Research Symposium on Aug. 1. The Rhode Island IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence program started in 2001, […]